What is Violin Rosin and How to Choose it

Rosin is also known as colophony and is used by string players to coat their bow hair. The resulting white powder grips the string and makes it vibrate and then sing. Without rosin, a bow wouldn’t make any sound at all. It would only slide silently over the string. This is how rosin is important for a string instrument, although it is often overlooked. If you want to get the most out of your instrument and get the best tone, learning everything about rosin is a must.

- History of the rosin

- How does a bow produce sound?

- Is rosin important?

- How is rosin made?

- How often should I change my rosin? Can it go bad?

- How to rosin a bow

- Can I mix and match rosin?

- How do I choose my rosin?

History of the rosin

The violin comes from a distant ancestor in the Far East part of the world. From India, travelers have brought it back along with them with several other musical instruments. They eventually made a halt in eastern countries. At that time, bow instruments used sheep gut strings. The bow was concave (like a hunting bow) and strung with a string made out of sheep gut as well. That gut has been hardened and dried under the sun. Its surface is uneven and rough enough to strike the string. But a bow made out of sheep gut is not solid enough. Some tried and improved upon it. Later, horsehair was used to replace gut strings in bows (gut strings have been used in violins far longer after that, until today).

But horse hair needs an additional grip to strike the string enough: natural pine sap has been chosen. People have been using that compound for a long time to glue things, to waterproof boats or roofs. Its sticky quality is perfect for a bow. Once coated on the bow hair, it grips and beautifully makes the string sing.

How does a bow produce sound?

The bow slide on the string, and the heat produced by the friction melts the rosin. The rosin then cools down. The string is glued to the bow’s hair for a short instant and released when the tension is too strong. The string then vibrates, the bow slides on the string, and the process builds up again. The bow works as a thousand guitar picks on the string. This tension-release mechanism, melting-sticking, stick-slip has been deeply studied by the german engineer Helmholtz. He described how what we see as a vibrating string with the naked eye is in reality an angle running through the string in a timely manner. That angle should travel back and forth in a synchronized fashion with the stick and slip timing of the bow (source courtesy of Stanford University). If we sum up without being too technical, a bow hair sticks and releases the string a bit like a guitar pick, but a thousand times a second.

Is rosin important?

There isn’t any sound without rosin. Without rosin, the bow would glide over the string in silence, which is quite surprising to hear. Every time a bow is re-haired (or is new), we can experience it. Rosining a bow for the first time is quite a long process, as there is no rosin to start off and stick to the rosin cake itself. See my blog post on how to rosin a bow for all the details.

That is why rosin shouldn’t be applied too quickly: because the friction makes it melt on the bow and the surface of the cake. Several bow hairs can end up glued together. It gives the sound a bad bow noise to it. A bow noise is something we do not want too much of it. When applying rosin, we should go medium speed back and forth four times, for example. To solve this issue, you can keep an old (and dry) toothbrush and brush the bow’s hair once a week to remove excess rosin and separate individual hairs sticking together.

Too little rosin is worse than too much. Because rosin is essential to strike the string, you risk having wolf tones or whistling E-string if you put too little rosin on your bow’s hair. So the correct rosin application can eliminate those bad sounds. You won’t have to change strings or alter your violin technique. So, never underestimate the role of rosin in tone production. If you work a lot on your tone and sound, it begins with good strings, good rosin, and perfect application of rosin on the bow.

Rosin is directly important in the type of sound you get on your strings. If the grip is too strong, the sound will be too harsh. The response of the bow will also be related to the role of the rosin on the string. If we strive for a quick emission and low bow noise, the best rosin has to go along with the best application. This is how it has to be done.

How is rosin made?

It is made out of sap from pine, but also from fir, nut pine, spruce, or larch trees (conifer trees). During fall, this sap is gathered and then heated up. In a boiler, water naturally evaporates. The sap becomes a liquid, and hard components fall down at the bottom of the boiler in a refining process. The top part of the pure liquid resin is cooled down. This resin can be diluted into alcohol (that is how we can clean it up from instruments, remember) or oil.

If the resin is distilled, the resulting distillate is called turpentine oil.

This resin is heated up again and mixed with oil and other ingredients that manufacturers keep secrets. Often beeswax, turpentine oil, or gold flakes are added. It is then cooled down again into what is called a cake. That is why each rosin has a different sound when gripping the strings.

The raw material is essential. In North America, for example, the sap gives a light and gold rosin. On the other hand, in Northern Europe and Germany, the rosin tends to be darker and brown.

This interesting video shows how to make turpentine oil and rosin out of pine sap in a simple way.

Can rosin go bad? How often to change rosin?

As we have seen, rosin is made of pine sap and solvent. The ethereal oils contained in the rosin dry out, and the rosin slowly changes its chemical properties. So it is difficult to know when to change rosin. I would say six to eight months if you are a professional, or every year if you are a student. It is difficult to attribute a bad sound to old rosin. But the least a violinist can do is:

- refresh the rosin cake with 400 grit sandpaper every week. Slightly sand off some rosin to access a fresher part and get some rosin dust. The heated and melted surface is sanded off. Then it gets the grip going and allows you to gather fresh rosin dust onto your bow hair.

- do not use a broken rosin cake. A sharp angle can deteriorate the bow quicker by wearing down the microscopic scales, thus weakening the hair. There is no way a broken rosin nugget can rosin your bow correctly and give you a good sound. So you have a great bow. You keep your bow hair in good condition. You need a new and fresh rosin cake, smelling good if you want to get the best sound out of your instrument.

How to rosin a bow

Usually, it is recommended to rosin your bow every time you practice if you play for a long session. If you practice for a couple of minutes, there is no need to rosin your bow. But as it is worse to have too little rosin on your bow as opposed to too much, then it is advised to rosin your bow four to six strokes every time you practice. But there is a lot more to it, and I have dedicated a whole blog post on how to rosin a bow the correct way.

Can you mix and match rosins?

As long as you respect the same type of rosins (the same type of trees it is made from – for example, pine), it is perfectly possible to mix rosins. For example, you can mix violin and viola rosin from the same brand on the same bow. Dark violin rosin gives a great edge to the sound (four strokes), and lighter viola clear rosin gives extra warmth to the sound.

If you’re unsure of the type of rosin, mix the same brand and check on the manufacturer’s website for each rosin base. Is it made out of pine tree, larch tree? So it is perfectly ok to mix rosins in order to get a better sound or to accommodate different string types or weather conditions.

How do I choose my rosin?

Rosins exist in many different degrees of hardness and stickiness. Different climatic conditions, ways of playing, and instruments lead to different choices of rosin.

- Climate: heat or cold, humid (harder rosin) vs. dry. The rule is simple: the more humid the climate, the harder the rosin. In a cold climate, a softer rosin is best. Vengerov and Repin must have used a soft rosin in Siberia when they studied with Brohn. They used to practice with mittens.

- Playing style: heavy or light style.

Some musicians prefer softer rosins to play at home or in a studio and a harder rosin when in a concert hall. As a matter of fact, a harder rosin gives more edge to the sound and a better projection; a softer rosin is better in conditions where a microphone is put close to the instrument and is more likely to amplify the bow noise close to the bridge; - Type of strings: steel strings prefer a hard and dry rosin, but gut and synthetic rosins work great with softer rosin.

- Instrument size: the bigger the instrument, the softer the rosin has to be, believe it or not. This has to do with shorter and higher-pitched strings have a stronger tension, while bigger and lower strings are less tense.

| Size | Rosin type | Humid | Dry |

|---|---|---|---|

| violin | harder | harder | hard |

| viola | hard | harder | soft |

| cello | soft | hard | softer |

| bass | softer | soft | softer |

So, when you have decided on the type of rosin you want for your instrument, your musical style, and your preferred strings, you need to adjust for the climate you live in, the season, or where you travel to.

That is why mixing rosin is a good practice because it is a simple way to adapt to the conditions.

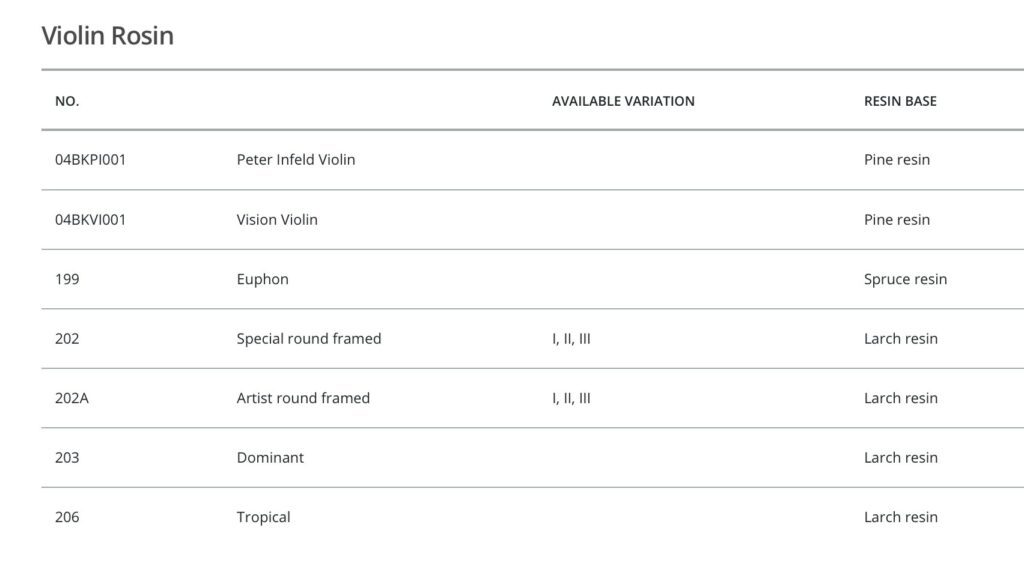

So, for example, you use the great Evah Pirazzi synthetic core strings. You can then choose the Evah Pirazzi gold rosin, that has been specifically engineered for these strings by the same people who did the strings. A soft rosin perfect for synthetic strings and an excellent sound projection. You can add a bit of hardness to it in the conditions specified above and choose some Tonica or Even Gold rosin (see the chart from Pirastro).

Thomastik-Infeld has a wide range of rosins: 17 of them. They give a complete chart spreading out their rosins (source).

I have explained my preferred rosin on my recommended products page: these are the rosins I recommend to my students and we have tested over the years.