How to Practice Effectively your Violin: 12 secrets!

If you ever want to be a great musician, professional or not, it all starts with practicing. It is that important. There is no way you will be a good violinist by just watching, listening, and mimicking. But when you are all alone, you probably don’t know where to start. Maybe you are not happy with your teacher either. In any case, the result you expect might not be there, and you wonder why. There is something you don’t do well in your practicing routine. You see people around you making tremendous progress. You’ve heard teachers or musicians saying: “it is not how much you practice; it is how you practice”. Well enough, where do I start? What am I doing wrong?

This is because practicing and maybe learning, in general, is often counter-intuitive. We focus on things that are not important while forgetting what matters. We study and instead get bad habits: we lose time.

How to practice effectively the violin or any other instrument

Table of content

- Put yourself in a practice routine

- Prepare what you have to study

- Don’t just repeat over and over again

- Don’t mix technique with music

- Practice always in tune with a good sound

- Don’t let any glitch; otherwise, you will practice glitching

- Vibrato or not?

- How to practice for concerts or exams?

- Tempo: always practice with a pulsation and metronome

- Practice what leads to difficult parts as well

- Don’t practice for too many hours

- Fast and virtuosic passages

- The last trick: practice without the violin

I remember, when I was a child, my teacher used to tell me to repeat that study 10 times. She didn’t tell me what technique to acquire, what to do when I succeed, what to do if I didn’t. So I only focused on counting while playing. This example is typical of the wrong ways many students practice or even teachers teach.

It is several years later that I met the man who was to become my mentor. He was a pupil of Leonid Kogan and was taught the great Russian school principles. He taught me the good way, and with fewer efforts and frustration, I was able to leave my bad habits behind and make great progress. I wasn’t even aware that I could play that well one day.

Here are in that blog post the best 12 tips he taught me during those years, together with what I’ve learned reading the great Galamian and Yankelevitch.

1. Put yourself into a practice routine

To tell your subconscious brain that you are practicing, it is good to create a practice routine that will be the same every day. Prepare your violin, put rosin on your bow, wear a comfortable shirt, shoes… Serve yourself a cup of coffee or tea.

Here is a little example of a routine.

Prepare what you are going to play. Play your warm-up routine, then scales and sound production, studies, and pieces, to finish with your old repertoire to keep in your fingers. Whatever you decide is best. But creating and keeping a routine is essential. If you break it up into several different parts, time will fly by; you will always know what to do and never lose time. You will, of course, adapt your routine to special weeks (a concert maybe) or a special difficulty to overcome. But your practice routine will be a spine that will hold your body all over the years. It will help you build up your technique and repertoire. It is a mental structure that will prove to be crucial.

2. Prepare what you have to study on your instrument beforehand

When practicing, you exercise your brain more than your fingers. So, don’t just pick up your violin and play blindly unless you only want to enjoy music and do not intend to progress.

Open your studies book and read it without the violin. Visualize what is important, what is difficult. Play the fingerings on the table. Mimic the bow strokes. Try to understand what the composer wants, what he or she has written the study for. A study piece is always written to emphasize and illustrate one technical point. If your teacher didn’t tell you, it is crucial for you to guess it. So before you start practicing, you will start wiring your brain to the difficulty to overcome, the technique to acquire. You won’t play blindly.

The time you don’t play, preparing your practice will be better spent and maybe more useful than jumping on the first bar with your violin in hand.

3. Don’t just repeat over and over again

Now that your practice is prepared already, you know that you don’t practice for the sake of practicing. You need to acquire one technique or get over one passage. That is the point. So don’t just play over and over again the same passage. Brake it up in smaller individual parts where one difficulty exists at a time. If, for example, you need to practice a new bow stroke (staccato), you can play with open strings and not with the printed notes. But you will practice thinking about what to acquire and not counting the time you spend practicing. This little mental twist has proven to be liberating.

Now that your mind (that you exercise, not your fingers, remember) is focused on the difficulty and not vaguely on the whole study, three outcomes are possible:

- you just can’t do it. So there is something wrong. Ask a friend, a teacher, outside help. But playing over and over something that does not work at all is discouraging and frustrating. You risk quitting all-together;

- you are better and better at it every day. My teacher used to tell me that most techniques are processes. They are acquired gradually, so we mustn’t fear them. In that case, there is no need to play a new bow stroke too much; you only risk being tense and play badly (being used to playing tense is bad).

- the technique is known. So don’t count repeating. Just play a couple of times to maintain your technique or to support your memory.

Points 2 and 3 don’t use much energy. You need to understand the process that leads from acquiring a technique to maintaining a technique. Acquiring is a gradual process that can’t be forced to fruition in the first days, so there is no need to force practice. Maintaining a technique doesn’t require hours of effort.

So don’t just repeat: know if you build up or maintain.

4. Don’t mix technique with music when you practice your instrument

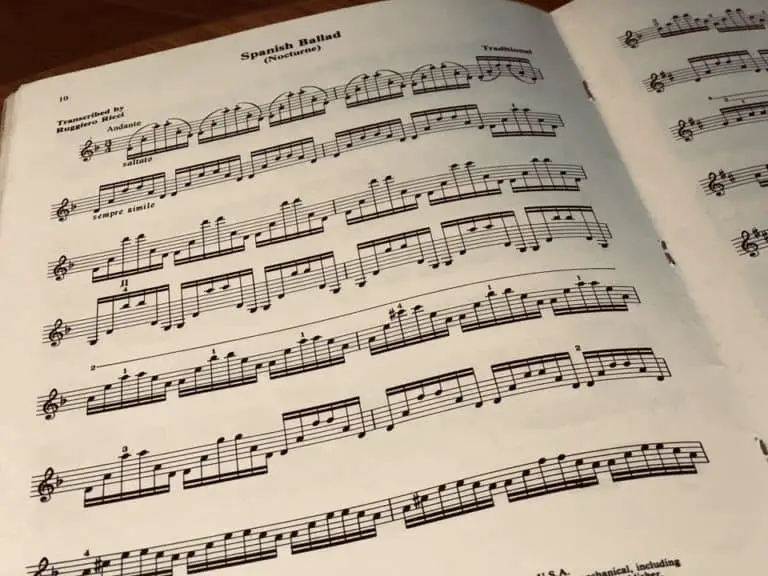

This can be debated. But I was taught not to mix technique with music. That is to say, if your technique is lacking (for example, saltellato), you won’t acquire it playing the 5th Paganini Caprice. Practice elsewhere the technical difficulties. They will become flesh within the actual musical pieces. Then, play them musically.

5. Practice your violin always in tune with a good sound

Practicing is building up neuronal connexions. They can’t be changed willingly on the spot. So if you get used to practicing with a lousy sound, over the strings, and bad intonation because, well, you were just practicing in your room to play a piece, then you will play your exam or your concert with a lousy sound and bad intonation. There is no way that, under pressure, you will hold yourself and tighten up your technique. You will play not only what you practice but how you practice.

Do not procrastinate on intonation. If you think briefly in your play: “this passage sounds great, but that note was a bit off, I know, I will fix this”, then, the day of your concert, the little voice in your head will go: “Oh, sh*t, I should have fixed that, I am such an idiot”. That has occurred to me, but no more.

So always practice with a good sound and a good intonation. That is how you will eventually play.

6. Don’t let any glitch, otherwise, you will practice glitching

If I go even further with the same idea, if you don’t correct a glitch and still play it, that means you practice playing like that. I couldn’t emphasize that more: if you don’t correct yourself at the very beginning, you essentially practice playing bad. And the risk is, as Yehudi Menuhin put it, you will get used to your own odor. That means you won’t even notice it anymore. That’s how bad it is.

Maxim Vengerov said it. He is the student of the great Zakhar Bron, who is a fine virtuoso but maybe, more importantly, one of the greatest violin teachers ever.

So don’t let technical deficiencies for tomorrow. You might just not see them anymore, being used to getting around them.

But, if you can’t let any glitch because you fear practicing to play badly, how can you even practice? Well, I was taught to play perfectly easy pieces rather than trying to impress friends and family with difficult pieces I could hardly play. Then, every week, I increased the difficulty progressively. You will focus on one challenge at a time.

7. Should you vibrate when practicing your violin?

In the same vein, I am in the school of thinking that practicing with a controlled vibrato is best. Why? For the same reasons that I have explained above. Unless you practice a particular technical point, vibrato is part of the expressive vocabulary of violin playing. It is part of it, not an embellishment you add on top at the end. A good vibrato has to be consciously varied and not automatic. To be beautiful, a good vibrato must be essential and part of the piece. So, even if you practice slowly, or even if you practice scales, some vibrato is important for your ear, for musicality, for building up reflexes.

It is hard to draw a definite line between musicality and technique. And let’s not forget by practicing, you are building up brain connexions. So if you want your vibrato to flow eventually during your concert or exam, play every day with it.

8. How to practice your instrument for concerts or exams?

This is a little psychology tip that can be crucial. Read on; you might be surprised.

When you practice for your exam, you practice in your room, in the clothes you’re used to, at the time you usually play.

For your exam, you need to get up early, wear a suit or dress in tight shoes, eat early, take a bus, play in a strange place with people you don’t know, at an hour you’re not comfortable.

There is a small difference here. Your brain will receive so many signals that will add up with pressure and stress and might hinder you from playing. Sweaty hands, shaking hands, stage fright, speeding heart…

So how to mitigate all those disadvantages? Well, you can’t have an influence on all of them. But you can, the week before your exam, prepare yourself already for that day:

- you wake up at the time you will have to;

- you take the breakfast you will eat;

- you dress in the suit/dress AND shoes you will wear for the exam;

- you go outside to take a bus or for a drive;

- you go back home and do your warm-up routine;

- you come into your room saying “hello” as if there was a jury;

- you eventually play your repertoire.

Then, later in the day, you can relax and practice the parts that need to.

Your subconscious mind and your body will adapt to those new circumstances, and the day you will play, you will feel less strain, less tension, and less stress.

And, a bonus tip, you can even go to sleep at night, envisioning the jury, what you will say to them, how you will look at them. Preparing for these details is essential as in the last week you won’t acquire much technique anyway. So if you can be at ease without stage fright and shaking hands taking the most out of your play will be far better than focusing on the violin only.

9. Tempo: always practice your instrument with a pulsation and metronome

The beating heart of the music is pulsation. How you play notes around the beat will give your piece its life.

Lastly, time is relative: difficult parts always appear slower; easy parts seem quicker. It is the other way round for some individuals.

So it is crucial to play with a metronome to acquire a regular tempo that goes throughout a piece. You can keep track of your progress by writing down the numbers.

Again, as practicing is connecting your brain, you shouldn’t indulge yourself with an elastic tempo. You will get used to it, practice it. You won’t be able to play with other musicians, and your music will lack life. Pulsation is first acquired with tempo and tempo with a metronome. Freedom will come later, and it will be able to come around the pulse because the pulse is there and felt within.

So, as you need to practice with a good sound, in tune, without known glitches, with vibrato, you need as well to practice with a metronome.

10. Practice what leads to difficult parts as well

So we’ve seen to break up pieces into parts, to see where the difficulty comes from, to extract them and practice them in dedicated studies, to perfect the required techniques elsewhere, to play with musicality from the start.

But it is important not to practice a part alone without the leading notes. If you study a position, then you have to incorporate the shifting as well; if you practice double-stops alone, then practice what leads there as well, to be mentally and physically in the needed position. The easy leading notes are part of the difficulty and thus of the practice. The bridge is as important technically as psychologically. So you will end up practicing more shifting than you thought you would. But things have to flow, and flow has to be prepared.

11. Don’t practice your violin for too many hours

Don’t practice for too long. Remember, by practicing your violin or instrument, in reality, you exercise your brain and train it to acquire new reflexes. So, as soon as you feel your concentration vanish away, it is time to put down the violin. Take a walk, some fresh air, a coffee, a yoga posture, I don’t know but take a pause. If you don’t, your mind will dream about something else, and your violin will be on autopilot. You won’t play the right way (notes, intonation, and so on), and, again, you will actually practice playing badly. And, if you play for too long, your arm will eventually stiffen up, your elbow contract, you might get a cramp. Now, this is bad. You don’t want to do that because your sound will be horrible, and the result of your practice will be counter-performing. You will again practice playing the wrong way. To know how long to practice every day, read that article where I detailed how long for each type of player.

12. Fast and virtuosic passages need special attention

These small parts have to be “in the fingers”, that is to say, a reflex in the brain, without a thought. The tip is not to play them for long periods but to maintain them constantly. They have to be played constantly, bit after bit, in the morning, in the evening, before lunch… for a brief period, a couple of notes, a couple of minutes.

My teacher’s teacher, Kogan, once told him that, when he was rehearsing with Sviatoslav Richter, he was amazed at how he practiced difficult passages. He played them all the time, every time he went by a piano, for ten or twenty seconds only. Igor Oistrakh once said that his father, the great David Oistrakh, played the most difficult passages just after waking up, even before any coffee, shower, or phone calls.

So virtuosic passages are different from music; they are a kind of ability to acquire and work well when they become reflexes. So the trick is to consider them as such and maybe extract them from your practice routine. A bit always, many times a day.

13. The last trick: practice without the violin

If you count properly, I have promised 12 tips, and I give 13… Well, I won’t develop this one here. But it is the crème de la crème. Only a true master knows it and performs it. Since you know that the important part is to exercise your brain, you can do it on a train, a plane. You close your eyes, think of the score, the music, and play mentally the shiftings, fingerings, dynamics… You will be amazed by the result. No more time is wasted in public transport, and your mind will become a violin.