How to Improvise on the Violin: 6 Quick Tips

Many musicians grow up feeling the need to free themselves from the score, whatever musical style they play. They want to improvise on their instrument. It is always a way to become a more complete musician. It gives the ability to better know their instrument, to better understand the music. Isn’t improvising composing on the fly? So, if you’re like me, you want to add that ability to your play. But this is easier said than done. Like many musicians, I was stuck when I first tried to improvise. So here is how I did it.

Table of content

- Why improvise on the violin?

- Do classical violinists and musicians improvise?

- Why many musicians are stuck and can’t improvise

- Tips and advice for general attitude towards improvisation

- How to start to improvise on the violin: a simple method

- Stack arpeggios on top of chords on the same tonality

- Use pentatonic scales

- Use chromaticism in scales, for themselves, in pentatonic scales

- Try to create melodies on the fly, structure your improvisations with questions and answers

- Play another chord on a chord

- Structure your improvisations with questions and answers

- Conclusion and general tips

- Complete score

Why improvise on the violin?

Why I wanted to improvise

I had been playing the violin (classical violin) for 12 years when I started to listen to Miles, Coltrane, Grappelli. Naturally, I wanted to improvise on my instrument as well: I was so shocked by the freedom and the beauty of improvised music. The great Yehudi Menuhin himself got closer to Ravi Shankar and Stéphane Grappelli to feel and taste that freedom. I don’t compare myself with such a giant, of course, but he influenced me as well into trying new sounds and colors. Of course, I still loved (and still do) classical music. Classical music shouldn’t be considered and or played as cold fixed music, and the improvisational type of playing you learn can be very helpful. The improvisational feel of cadenzas, of course, but the types of ideas you get when you learn to improvise on a chord are very interesting and important to interpret great musicians such as Bach and his major work, the solo sonatas.

So improvising on the violin has several major benefits. It allows you to open your ears and your mind to new sounds and colors; it gives you the freedom to play whatever you want on any chord and any type of music; it frees you from just reading and playing music; it gives you a greater insight on how and why composers have written the music they have; it allows you to play in different kinds of bands: overall it just makes you a better musician.

Do classical musicians improvise?

In the history of music, great composers were also great musicians and performers. They could play and improvise their part very well, including on the spot during a concert. J.S. Bach was a brilliant organist and used to make great improvisations, some of which have been written down a made into a piece. It is the same with Beethoven: he could play the piano incredibly well and improvise. If the piano part of his concertos was not ready in time for the concert, he just improvised part of it on the fly in front of the audience. He then wrote down and developed his best ideas. During the baroque era, violinists used to improvise, modify, and embellish the work they played. Mozart himself, though it is still debated, wrote pieces so bare and minimalist that musicians think they were a base for improvisation and embellishment. Cadenzas are the free part given to the performer by the composer at the end of each movement. It is designed to be improvised, like a jazz chorus, and show off the soloist’s virtuosity and inventiveness. So improvising has always been a part of music, and if classical musicians don’t know to improvise anymore, this is not due to tradition, on the contrary.

The roadblock I immediately hit when I started to improvise

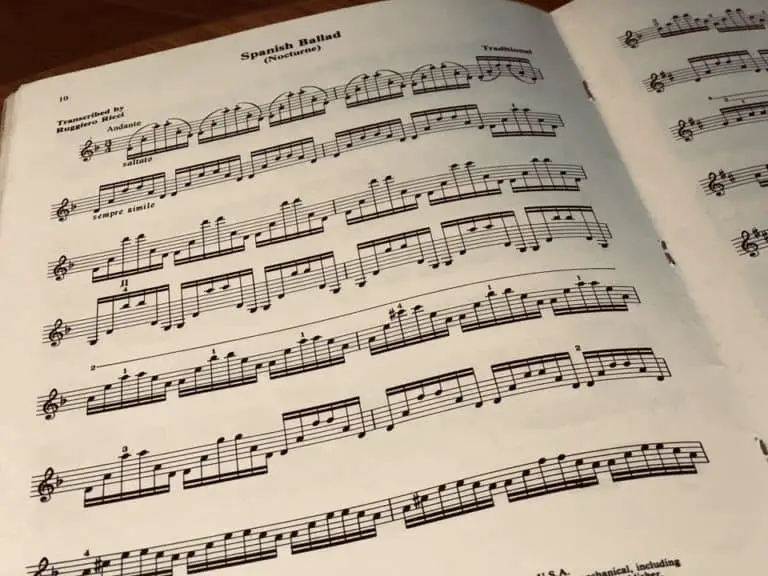

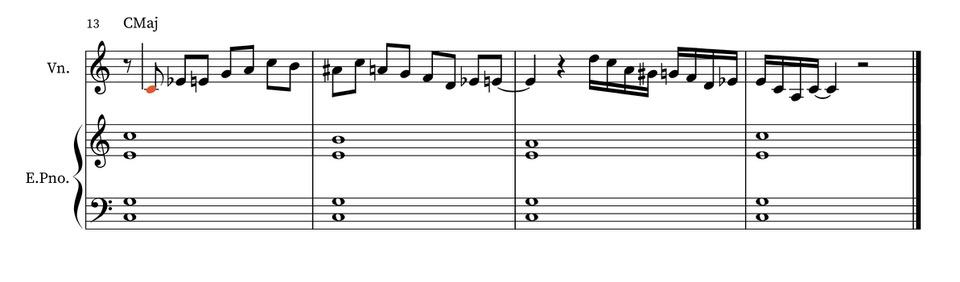

So I decided I wanted to play like Grappelli and Miles… So I invited friends at home, I remember, a guitarist and a saxophonist. We played a tune, maybe a blues, and it was in C. I still remember being stuck! My brain was just frozen. I started to play the C scale, which sounded ridiculous, so I added a couple of intervals for a change. Then I thought I couldn’t play that on C. So I stopped. I played something like this:

So I felt stuck, like many people who try to improvise the first time. I was very deceived, a bit ashamed, and thought I could never do it. I wanted to quit.

So the problem was not in my hand (I had a good technique), but in my mind (nothing was created there to be played).

So I would like to help and give simple and practical advice to any violinist, or any other instrument, of classical upbringing or not, to start and “free his or her playing”. At least, this is what I did and how I started.

Tips and advice for general attitude towards improvisation

I couldn’t improvise because:

- I didn’t think I could play a melody,

- I over-analyzed chords and harmony and felt I was making musical “mistakes”,

- I had no prior material I could use: improvising can be prepared,

- I couldn’t embrace being “free”.

So I will detail how I could overcome these limitations.

How to start to improvise on the violin: a simple method

The tips I am about to give are directed at beginners mainly even though there are some more advanced topics.

1. Stack arpeggios on top of chords on the same tonality

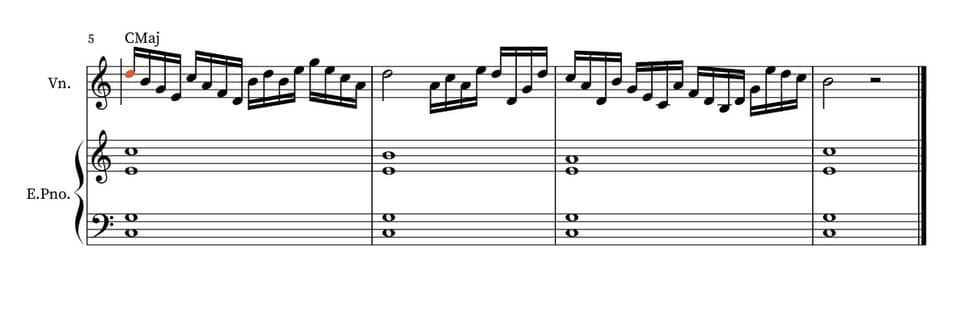

Chords can make or break: they deter the musician from improvising. We’ve learned about intervals, arpeggios, and chords, and we get to be too analytical about what we play. This is a kind of analysis paralysis. For example, I used to think that on a C chord you could play an E (third) that sounds great, but maybe not an A (sixth) because the note A is not typical for the C tonality. What a misunderstanding, an A pupil mistake. Of course, you can play any note of the scale of C in C, some notes are passing notes, others need or can be emphasized. You can play as well any arpeggio you want on C starting on any note in the key of C. Here is an example of freely playing C notes over the C chord:

This is already far better than the first way of playing that I wrote above, don’t you think?

So feel free to use any scale note you want, quickly or slowly, on the chord you play on, just be aware of the note you land on and emphasize.

Try to improve on that. You feel already freer, don’t you?

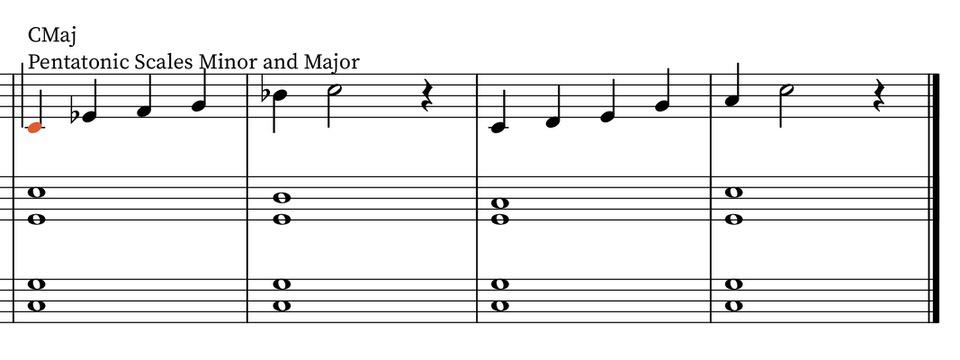

2. Use pentatonic scales

Pentatonic scales are everywhere today. Especially if you are of classical background, you are not used to them. They can be very useful in any kind of music you intend to play and you must master them. Of course, if you want to improvise on classical or baroque violin, they will be less useful. But if you want to play jazz, rock, blues, folk, or bluegrass they are compulsory. I can’t stress it more.

There are many pentatonic scales. In the case we study, that is to say, improvise on a C chord, there are two, like in blues and rock in general:

- the pentatonic minor scale;

- the pentatonic major scale.

The Blues usually uses the minor scale (with a twist) and folk and rock music the major one. But they are often mixed with one another in the most fascinating way.

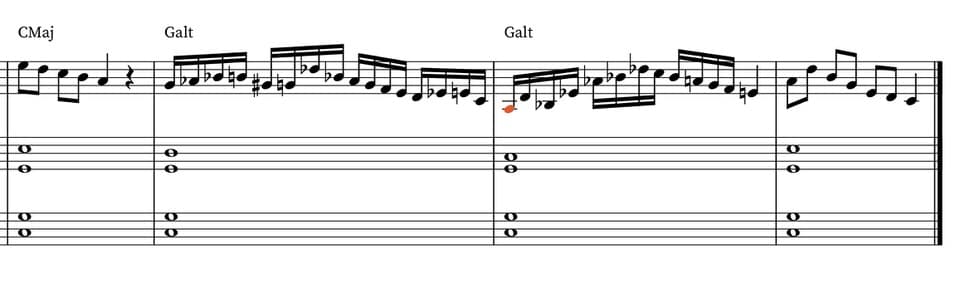

Let’s see what we can do with them in the context we are interested in. This is what could be improvised over the C chord using pentatonic scales :

The last phrase mixed pentatonic scales and arpeggios on the C scale. This is what you should always do unless you intend to play die-hard blues: mix diverse material to enrich your play.

Alright, now that you spiced up your play with pentatonic scales, you sound more modern, more rock, more blues. You can work on this and be part of a band right now. But let’s how you can enrich yourself, even more, your play to be more aggressive, varied, and original.

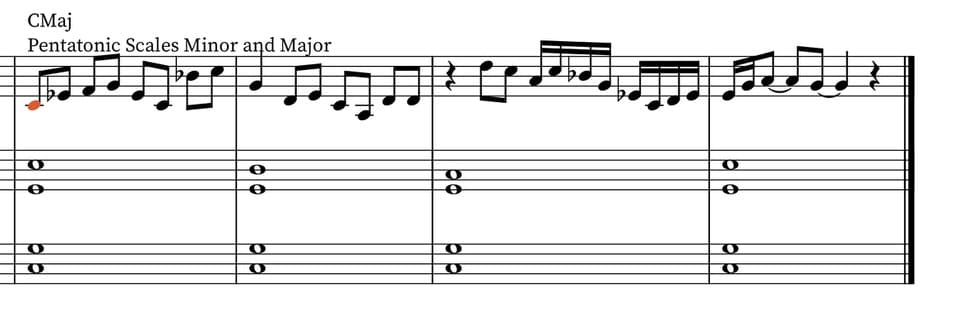

3. Use chromaticism in scales, for themselves, in pentatonic scales

If you only play notes from a scale (major scale in C or C pentatonic), chances are your play sounds a bit dry. It lacks something to spice it up. You should use chromaticism. Anyway, you would quickly find out that no pentatonic scale is used without chromaticism, even in the busiest blues:

Even in the case of our C scale, chromaticism gives a nice sound. Those chromatic passing tones are typical of jazz but are also used in classical, blues, and rock. Chromatic tones are technically out of the scope of the tonality we play in; but never mind: what is important is the note we land on. This is what defines tonality. Here is an example of what can be played on our C major tune, using pentatonic with chromaticism.

That sounds richer, more complex. It is suitable for jazz and rock or anywhere you feel like playing it. In any case, it is a new element of your play that you can use at will when tension rises maybe.

4. Try to create melodies on the fly, embellish a theme

Now that you know how to use scales, arpeggios, and chromaticism, you get the feeling that your improvisations sound always a bit the same. This is because you always use material without taking the context of the tune into account. You gain more experience, you start to be more at ease. Now let’s forget scales and chords for a while and concentrate purely on music.

Improvising is a quest to be free; but how more free can you get than playing a theme and a melody each time in a different way? The melody of the song and the theme of the tun, are important, or even crucial, parts of the musical ideas that can be developed. It brings beauty, life, and air into what you play. It is contextual. You won’t play always the same scales and riffs anymore. You can start playing the melody of the tune with small twists, embellish it, and complicate it; you can play it with different notes, and different intervals. Then your whole improvisation can revolve around it. This is very powerful and inspiring.

You also can create a second melody, like a B theme, that responds to the main melody. It is often used by composers (the orchestra plays the A theme, the violin starts with the B) and the beginnings of great improvisations by jazz giants, such as Miles, have become a theme on their part.

So, it is crucial to think also in a melodic way; to alter, use, and play with the melody, while never losing sight of it, but also to create our melody like an answer, a counterpoint to the main theme.

5. Play another chord on a chord: G dominant (altered) over C to give the illusion of a harmonic tension-resolution pattern

I said that it would be material for beginners, and this is getting pretty advanced. Nonetheless, I wanted to stress that point, because it can be easily heard if not understood: you don’t have to play in plain C on C! Without leaving the C harmony, you can oscillate between C and G dominant (altered) which is the tension chord of the C tonality. Every C tune has a passage in G, like a suspense chapter before the end of the novel. So, even if only C is written on your score, you can play G resolving in C any time you want. It gives your improvisation a sense of tension to resolution, dissonance to consonance, stress to relaxation, complexity to simplicity, and suspense to resolution. Our ear or our mind is used to it, to understand the logical reasoning behind it. It gives an improvisation some great spice and interest, especially on a repetitive chord. Here is how we could play in our C example:

Don’t over-analyze it. It has its own logic to it, and, if not plainly understood, is accepted and felt by the audience.

So a tension-resolution pattern translates into G altered towards C in our example, on C.

6. Structure your improvisations with questions and answers

Don’t forget also that you don’t need to start a linear improvisation, with the theme towards a more complex and virtuosic passage. Like many composers, you can alternate your phrases in a question-and-answer structure. You can start an idea, respond with another, and complement the first again as an answer. Ideas can be opposite (rhythmic for one, melodic for another), respond, and mix. The way you can elaborate is endless. If the development of the two (why not three?) ideas is simultaneous, it is called counterpoint. It is used by some musicians but is particularly difficult to do on the fly. But intricate lines that give a unique monodic line are a beautiful way of developing an improvisation. That structure, based on question and answer, and contrast between melodies, is used a lot by great improvisers and great composers (Mozart for example).

So this is not technical advice but more of general guidance on how NOT to sound like playing scales.

Complete score

This is the complete score after each iteration, from simple to complex. You can grab any material you want to enrich your improvisation:

Conclusion

- Listen to musicians and try to get ideas: you can’t play what you don’t hear in your head. So improvising is not in your fingers. It has to be part of your musical culture. So listen to as many musicians as you like to inspire you. You will get the feeling of how to play, and what to play. You will forge your ideas.

- Be free, don’t fear making mistakes. It is by making mistakes that you will free up your violin. You will play something and think:” this sounds great” or “that sounded horrible, I won’t play it again”. Your ear will be your judge as long as you continue to educate your ear with your technique. Remember that Miles once said that there is no such thing as a wrong note.

Keep on playing! Improvising is good not only for jazz but for classical, cross-over, bluegrass, rock, pop, Irish music… The sky is the limit, and your journey will be passionate and endless.

Now check out my article on how to play the blues on the violin. It is a great complement to this one.